The Princess Bride (to Be), Across the Sea, and the Importance of Story

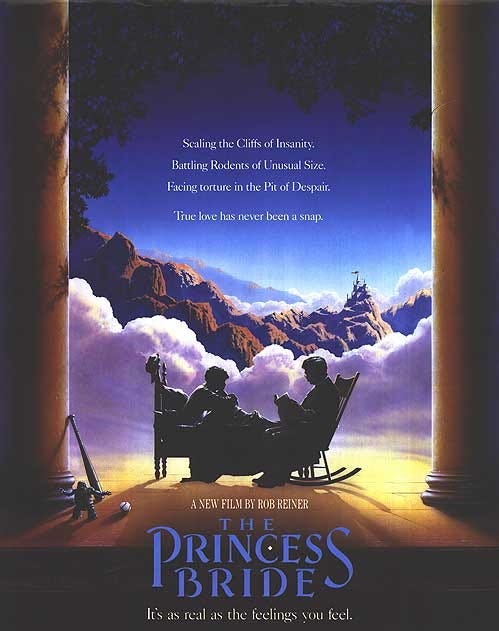

I asked my wife to suggest a timeless movie I could write about for my first Substack article. I’ve written articles and a book, so you wouldn’t think I would put such pressure on myself but I wanted it to be special. Her first proposition was The Princess Bride. Perfect! But how would I give you a fresh take on a classic? After all, many believe it’s a perfect film, Cary Elwes (Westley) wrote a behind-the-scenes book, and Ryan Reynolds did an amazing, self-aware homage in Once Upon a Deadpool (2018).

So I re-watched The Princess Bride and prayed for inspiration. Sure enough, as with any great storytelling, inspiration hit. I realized the book’s author and screenwriter, William Goldman, didn’t just create a great story - he was a great storyteller. And I figured out why effective storytelling satisfies a life-sustaining appetite in all of us. Wanna know more? As you wish!

(Story)telling

Components of a story, such as plot, conflict, and resolution, seem to get a lot of press. But the telling of that story is even more complicated. Good storytelling is easy to understand, feels natural, and pulls you into the world. But, in my opinion, great storytelling has a simple premise (even if portions are complex), witty dialogue and/or narration, and contains surprises or unexpected events.

But why does great storytelling nourish and impact us? I believe an acute portrayal of emotions, motivations, and psychology are integral yet so elusive. The Princess Bride is a great story - it’s told so well the audience relates, not necessarily with battling people like Iñigo Montoya or Fezzik, but with the character’s emotions and subconscious psychological drives (like Coco and The Breakfast Club). Additionally, viewers are pleasantly surprised - the vast majority of Westley’s screen time is spent getting out of impossible situations (like The Martian). And we’re enticed by the adventure - a swashbuckling journey to keep twue wuv (like Romancing the Stone) - and we do it from the safety of our bedroom, where Grandfather Peter Falk keeps our rapt attention.

Those components - relatable emotions, shared motivations, subconscious psychological desires, all imbued with surprises and adventurous escapism - are part of why great storytelling satisfies us. As a side note, getting invested in a character (even if we don’t like them) is also paramount. But the intangible parts of effective storytelling aren’t just stacked haphazardly. Like Buttercup and Westley’s love, great storytelling components always have a solid foundation.

Fable(d) Foundations

Creating new stories isn’t natural for me - that’s why I write non-fiction. So I’m jealous of those who create new worlds from scratch. Granted, there’s nothing new under the sun, therefore, much of creativity is homaging (i.e. ripping off) or re-working (i.e. avoiding copyright infringement) that which came before.

One part of being made in God’s image is that He made each of us as sub-creators. We can’t create something from nothing like Him, but we can use our imagination[i] to make new things. That’s another reason The Princess Bride is so impressive - it begins with a solid foundation. The film is accessible because it doesn’t require our memorizing vast world-building or knowledge of mythic lore.

Yes, William Goldman wrote the story based on core, universal feelings and ideas. Sure, the script uses fairytale tropes like the helpless female (rescuing a princess), adventure (defending honor and fighting), journeys (across sea and land), and a perfect ending (“happily ever after”), but the metaphors aren’t belabored. Even though the film turns 35 this year, and some portions are very ’80s, Director Rob Reiner and Goldman created timelessness, keeping it from being cliché, allowing it to transcend tropes.

This is where the master’s touch is art. Like outsmarting Vizzini, Reiner and Goldman wink and nod at the symbolism, drama, and comedy, without being arrogant about their cleverness. As artists, they use the right pallet at the right times. When to use a joke or when to inject drama, but also when the moment should be epic and when to be intimate.

Can you imagine our introduction to Buttercup and Westley as a bunch of slapstick? It could be hilarious but would have undercut why Ben Savage’s grandson character was bored and hated the romance. Or what if they hadn’t allowed Billy Crystal to ad-lib most of his lines? How about the intangible authenticity gained by shooting on location in England? Similarly, books like Ready Player One and shows like Fargo and bands like Gloryhammer, are incredibly smart about making the legend momentous and the moment legend.

So a great story needs a strong foundation and a brilliant storyteller. But is that it? No. Both those components help us understand why we connect deeply with a legendary story, but we’re also actively involved. What could we possibly bring to the table?

(Story)listening

The proverbial storytelling table has two goblets, one with amazing stories, the other poisoned tales. I’m not saying we should go in against a Sicilian when death is on the line, but it’s up to us which we drink from. We take nourishment in the good stories by listening.

I had an epiphany writing this: Great stories can’t be appreciated without intentional listening. Duh, right? Well, it goes deeper than that. For example, I find it fascinating that 43% of the Bible is narrative. But what good is a good story if we’re not good at listening?[ii]

In The Princess Bride, the grandson gets bored when the story, especially the action, wanes, and the kissing stuff happens. Similarly, when deep theological ideas are talked about, they can be boring. Have you ever listened to a sermon or podcast where the speaker told a story you became invested in but when they transitioned to a complicated point or academic theory, you got distracted or sleepy? Sometimes we want the shortcut. (Anybody want a peanut?)

We’ve all been there and we’re not evil or unintelligent - humans just get bored. As John Mark Comer says in The Ruthless Elimination of Hurry, boredom can be a good thing. But, lest I get distracted, with great stories the onus is on both the presenter and the listener. A talented writer will impart crucial, sometimes complex truths through compelling narrative. But the audience must cultivate the practice of intentional listening. The skill requires suspending biases, quieting your mind, and paying attention to the other person.

Wait - great storytelling shouldn’t require a lot of work at listening, right?! Yes and no. Yes, by definition great stories and their telling, captivate us. However, our society currently has a pandemic of distraction. Nowadays, the most interesting story struggles to compete with a phone notification or with our attempts at “multitasking.”

I won’t go into a device detox rant here (check out my article noting permanent dangers of modern distraction and healing) but we should be mindful that if we’re built with a basic need to hear great stories, then robbing ourselves of those simply by being distracted is a fool’s errand. Seriously, try and sit through The Princess Bride without a device and without hitting pause. I couldn’t, it took me three days to re-watch the film just to write this article.

The epiphany I just mentioned was on how great stories can only be truly appreciated with intentional listening. This is where our deep need for impactful storytelling comes full circle. Core story structures are based on common feelings and ideas, and the very definition of active listening is to suspend biases to find common ground and focus on the other person! Inconceivable!

Is it possible that we don’t categorize more stories as “great” because as humans we inherently have trouble suspending our cultural understanding and biases and regurgitated storylines and even comfortability with character names? What can storytellers learn from being better listeners? And what can the audience learn from exploring great storytelling from other countries and mediums? I think we may be starving the very appetite that must be nourished. We’re literally made to tell and listen to stories.

Happily Ever Crafter

The Princess Bride is near-perfect and a prime example of great storytelling. The superb narration of Buttercup and Westley’s arc nourishes and satisfies shared emotions and psychological traits. As an artist, the storyteller must craft from a solid foundation to inform the audience’s experience. In this case, Reiner and Goldman created the experience but, by definition, it had to be experienced by an audience who truly listened. This is our exciting opportunity to be part of the craft, to have a shared responsibility in how active listening plays a crucial role in appreciating great storytelling.

Consider how that last bit brought about my epiphany on why great storytelling and active listening share many commonalities. I encourage you to seek out fantastic stories and excellent storytelling like The Princess Bride. Nourish that fundamental need in your soul. Will you do yourself that life-giving favor? And now you respond: As you wish!

Recommendations

I don’t get to list supplemental stuff I enjoy after my articles, so I’m excited to share these:

-The Princess Bride book by William Goldman. It’s hilarious. The film is outstanding storytelling and comedy but the source material is longer content of the same goodness.

-On Stories book by C.S. Lewis. I bought this book and plan to read it this year. Master storyteller (The Chronicles of Narnia) and apologist (Mere Christianity) C.S. Lewis explains how to write fiction. Apparently, it’s good for both authors and people who like to read cool stories. Bonus: Eleven short stories unpublished in Lewis’ lifetime.

-The video “Celebs React to 'The Princess Bride' 30th Anniversary.” It’s a fun three-ish minutes watching stars geek out about the film (gasp, they really are just like us!). My favorite might be Jake Gyllenhall impersonating Carol Kane and Billy Crystal, then cracking himself up.

[i] I find it interesting that in English “image” and “imagination” have the same prefix. “Image” comes from Old French image, as in “likeness or figure” and Latin imaginem (imago) meaning “copy, imitation, likeness.” The word imagination” comes from the Latin imaginari which means “to picture oneself.”

[ii] Because Tim Mackie first told me about how important storytelling is, it’s fitting I link to his co-created site, The Bible Project.